Stumbled on this awesome diagram of the history of time travel in the movies. I just wish they had used a logarithmic scale for travel so that everything before 1850 didn’t get lumped together. They also left out my very favourite time travel movie, Primer, but that’s okay, somebody else made a diagram of the convoluted timeline.

Category Archives: science

happy pi day!

Is it really Pi Day again already? Happy 3.1415926535897932384626433832795028841971. Happy 3.1415926535897932384626433832795028841971, everyone. I considered watching the movie Pi (which I love, even though it doesn’t have much to do with the number), but I couldn’t find my DVD. So instead, I watched Vanishing Point, which has fast cars and a naked hippie chick on a motorcycle.

Anyway, here is a proof of the irrationality of Ï€. (Proof of the transcendence of is Ï€ left as an exercise for the reader. Hint: first prove e is transcendental, then use Euler’s formula!)

In other news, the last few years of grad school have led me to the conclusion that advanced math is essentially a black hole into which time and self-esteem are sucked, and from which nothing good ever escapes.

Assume π = a/b with positive integers a and b.

Now, for some natural number n define the functions f and F as follows. Strictly speaking, f and F should each have n as an index as they depend on n but this would render things unreadable; remember that n is always the same constant throughout this proof.

Let

- f(x) = xn(abx)n/n!

and let

- F(x) = f(x) + … + (-1)jf(2j)(x) + … + (-1)nf(2n)(x)

where f(2j) denotes the 2j-th derivative of f.

Then f and F have the following properties:

f is a polynomial with coefficients that are integer, except for a factor of 1/n!

f(x) = f(Ï€-x)

0 <= f(x) <= πnan/n! for 0 <= x <= π

For 0 <= j < n, the j-th derivative of f is zero at 0 and π.

For n <= j, the j-th derivative of f is integer at 0 and π

(inferred from (1.)).F(0) and F(Ï€) are integer (inferred from (4.) and (5.)).

F + F ” = f

(F ‘·sin – F·cos)’ = f·sin (inferred from (7.))

Hence, the integral over f·sin, taken from 0 to π, is integer.

For sufficiently large n, however, inequality (3.) tells us that this integral must be between 0 an 1. Hence, we could have chosen n such that the assumption is led ad absurdum.

Blatantly stolen from here.

“statistics is unnatural and subversive”

Andrew Gellman posts a link on his blog to a great talk by Dick De Veaux about teaching Statistics, making the point that unlike math and music, but like literature, doing stats requires life experience.

Like a lot of math/science geeks, I went through a phase of my undergrad where I was caught up in the beauty and elegance of “pure” math. Now, though, I find statistics much more interesting. Not that I read myself to sleep with stats textbooks, and the more esoteric it gets the less interesting I find it, but I do find myself more and more looking at the world using the tools of statistics (and its dark cousin, economics). Pure math, like programming, creates a perfect, orderly universe that can be mechanically understood, but statistics gives us tools to make sense of a messy, anarchic universe without taming it. But in order to use stats, you have to first pay attention to its world and try to understand it. And then stats will show you how wrong you are.

another day, another paper

also known as "NIPS", originally uploaded by Mister Wind-Up Bird.

Paper writing is pretty stressful. Code crashes, mistakes are found in equations, and you never have quite the experimental results you want. As deadlines approach, the pressure builds and sleep is abandoned. But I kind of welcome them. And not just for the rare flash of “hey, I’m actually doing science!” satisfaction. A good, hard deadline adds some much-needed structure and discipline to the grad student lifestyle. It forces you to stop tinkering with code and equations and write that shit down. And having just submitted a paper is a great excuse to drink heavily and spend a few days watching movies and playing video games before going back to work.

The paper I submitted yesterday was for the rather grand-sounding Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. Or: “NIPS”. (For years now, I’ve been thinking about making various off-colour “I heart NIPS” T-shirts, and I swear, one day I’ll do it.) This is my fourth paper since February — the fifth if you count my PhD thesis proposal. I’m kind of looking forward to not writing another one for a while.

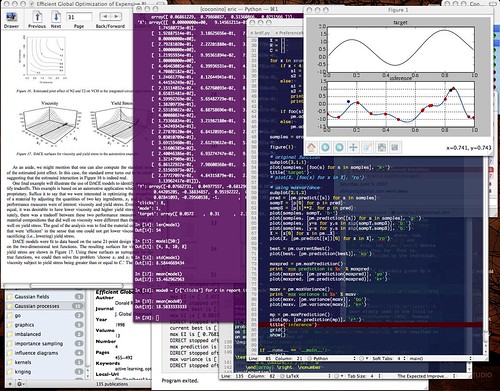

This screenshot is my work environment a little before the paper deadline. If you click on that there image, you can see the Flickr version, where I explain what all those windows are doing (more or less: it’s an anonymous-review conference, so I can’t say anything identifying about the research).

On a geeky note (well, even more geeky), I did all the coding, experiments and figures for this paper in Python using Pylab and SciPy, rather than MATLAB. After years of cursing MATLAB (generally by muttering “god, I fucking hate MATLAB” every time it eats up all the available memory and then crashes) and threatening to switch to something — anything — else, I decided I had to either put up or shut up. And shutting up is not my way. Python is not a perfect replacement, but I’m quite happy to report that it worked very, very well and I expect to do most of my thesis work with Python.

Erdős Number

Paul Erdős (1913-1996) was a mathematician probably most famous for being nothing but a mathematician, eccentric and brilliant even by the standards of that breed. He published over 1500 papers during his life, while for years he lived without any permanent address. He would crash with mathematician friends of his while collaborating, fueled by a diet of coffee and amphetamines, and occasionally collecting cash prizes for solving outstanding problems in math.

Paul Erdős (1913-1996) was a mathematician probably most famous for being nothing but a mathematician, eccentric and brilliant even by the standards of that breed. He published over 1500 papers during his life, while for years he lived without any permanent address. He would crash with mathematician friends of his while collaborating, fueled by a diet of coffee and amphetamines, and occasionally collecting cash prizes for solving outstanding problems in math.

Because he was so prolific and published so widely, as a tribute, his friends created the “ErdÅ‘s number“, a kind of nerd version of the Kevin Bacon game. ErdÅ‘s has a number of 0. People he co-authored papers with have a 1. People who co-authored papers with them have a 2, and so on. My ErdÅ‘s Number, as near as I can determine, is 5.

That’s right, ladies: buy disulfiram 500mg five.

- Paul Erdös, F Harary and Maria Klawe. 1980. Residually complete graphs. Combinatorial mathematics, optimal designs and their applications, Proceedings of a Symposium on Combinatorial Mathematics and Optimal Design; Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado, 1978, Annals of Discrete Mathematics 6, 1980:117-123

- K Inkpen, Kellogg S Booth, S D Gribble and Maria Klawe. 1995. Give and take: Children collaborating on one computer. CHI’95 Conference Companion, (Denver, Colorado).

- A Csinger, Kellogg S Booth and David Poole. 1994. AI Meets Authoring: User models for untelligent multimedia. Artificial Intelligence Review. Springer Netherlands. 8(5-6):447-468.

- P Carbonetto, J Kisynski, Nando de Freitas and David Poole. 2005. Nonparametric Bayesian Logic. Uncertainty in Artificial Intelligence 2005.

- Eric Brochu, Nando de Freitas and Kejie Bao. 2003. The Sound of an Album Cover: Probabilistic Multimedia and AI. AI-STATS 2003.

Actually, having a number of 5 isn’t particularly noteworthy, even for a student. What I think is interesting is the way that the connections spread not just through authors, but through fields. The first paper is a math paper. The second is about human-computer interaction (HCI): research on the way people use computers. The third is on user-modelling, which combines HCI and AI. The fourth paper is a stats-oriented AI paper, as is the fifth one (mine), though my focus is not theoretical, but applied. By this point we’re a very long way from the pure math of Paul ErdÅ‘s. I kind of like the idea of different branches of research being so tightly networked together.