I’m currently on my third straight day of being laid up with the flu. It hurts to walk and the idea of eating solid food makes me cringe, and also, I’m ever whinier than usual. On the positive side, though, in addition to watching innumerable hours of Star Trek, I’ve managed to squeeze in some excellent documentaries.

Heima is a concert/tour film from the Iceland band, Sigur Rós. In 2006, the band, having successfully toured internationally, did an unannounced tour of Iceland, playing in everything from music festivals to coffee houses to abandoned factories in near-ghost-towns. The doc mixes concert footage with starkly beautiful photography and snippits of interviews. The interviews don’t do much to dispel the band’s reputation for being aloof and prickly, but the music (all recorded live) is brilliant and… my god, watch this trailer and tell me you don’t want to go to Iceland.

Heima is a concert/tour film from the Iceland band, Sigur Rós. In 2006, the band, having successfully toured internationally, did an unannounced tour of Iceland, playing in everything from music festivals to coffee houses to abandoned factories in near-ghost-towns. The doc mixes concert footage with starkly beautiful photography and snippits of interviews. The interviews don’t do much to dispel the band’s reputation for being aloof and prickly, but the music (all recorded live) is brilliant and… my god, watch this trailer and tell me you don’t want to go to Iceland.

Actually, I saw this one the night before I came down with the flu, at the VIFC, and there was an interesting Q & A with the director, who explained the genesis of the film in a failed tour documentary that he volunteered to try to salvage. This explains some of the rough edges the film has (and, apparently, a lot of the landscape photography), but really, kudos to Dean DeBlois for taking what apparently was an unwatchable mess and making it into a really striking film.

The King of Kong is a different genre altogether — the crowd-pleasing, unabashedly dorky subculture doc (see also, Spellbound, Trekkies, Wordplay, etc.). It’s basically the story of a likeable loser and an obnoxious winner, and their not-so-friendly rivalry for the World Record score for Donkey Kong, a record that is almost literally a matter of life and death to them, and almost completely irrelevant to every other human being on the planet. I’m not sure it’s quite worth some of the rave reviews its been getting, but it is terrifically entertaining. (And after you see it, check out this fascinating interview with the film’s “villain”, Billy Mitchell, in which he comes across as even more self-absorbed but also more likeable than he does in the movie.)

The King of Kong is a different genre altogether — the crowd-pleasing, unabashedly dorky subculture doc (see also, Spellbound, Trekkies, Wordplay, etc.). It’s basically the story of a likeable loser and an obnoxious winner, and their not-so-friendly rivalry for the World Record score for Donkey Kong, a record that is almost literally a matter of life and death to them, and almost completely irrelevant to every other human being on the planet. I’m not sure it’s quite worth some of the rave reviews its been getting, but it is terrifically entertaining. (And after you see it, check out this fascinating interview with the film’s “villain”, Billy Mitchell, in which he comes across as even more self-absorbed but also more likeable than he does in the movie.)

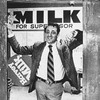

Being entertaining, though, is something that doesn’t even enter the picture in The Times of Harvey Milk, about the rise and assassination of one of America’s first openly gay politicians. It’s sombre and powerful, but like a lot of sombre, powerful docs, it’s kind of manipulative: Harvey Milk, a moderately competent local politician killed by a mentally ill man, is presented as a martyr for gay rights, and frankly I didn’t buy it. It’s unfortunate that they didn’t just let Milk’s life speak for itself, and let us see him as a decent man who was the victim of a senseless tragedy.

Being entertaining, though, is something that doesn’t even enter the picture in The Times of Harvey Milk, about the rise and assassination of one of America’s first openly gay politicians. It’s sombre and powerful, but like a lot of sombre, powerful docs, it’s kind of manipulative: Harvey Milk, a moderately competent local politician killed by a mentally ill man, is presented as a martyr for gay rights, and frankly I didn’t buy it. It’s unfortunate that they didn’t just let Milk’s life speak for itself, and let us see him as a decent man who was the victim of a senseless tragedy.

I still don’t have enough of a Bollywood vocabulary to put this in its proper place, but to me, this is what I think about when I think about Bollywood movies — 185 minutes of romance, elaborate dance numbers, and over-the-top, no-holds-barred melodrama. It also has some really striking eye candy, both in the sets — much of the movie takes place in a palace made out of coloured glass — and the cast. (Speaking of which, while Aishwarya Rai seems to be more internationally famous, in that I’d heard of her before seeing this movie, I found the scene-stealing Madhuri Dixit to be more beautiful, more charming, and a much better actress.)

I still don’t have enough of a Bollywood vocabulary to put this in its proper place, but to me, this is what I think about when I think about Bollywood movies — 185 minutes of romance, elaborate dance numbers, and over-the-top, no-holds-barred melodrama. It also has some really striking eye candy, both in the sets — much of the movie takes place in a palace made out of coloured glass — and the cast. (Speaking of which, while Aishwarya Rai seems to be more internationally famous, in that I’d heard of her before seeing this movie, I found the scene-stealing Madhuri Dixit to be more beautiful, more charming, and a much better actress.) The opening shot of Spike Lee’s Bamboozled features Damon Wayans, playing a thoroughly co-opted buppie television writer, nasally reciting the dictionary definition of “satire”. The movie ends with a montage of racist depictions of African-Americans in the media (take that, Birth of a Nation!). These two scenes probably tell you everything you need to know about what to take away from the movie. Namely that this film is a satire on depictions of Blacks in the media and their own complicity in the process, and also that Spike Lee thinks we’re all idiots. Fair enough.

The opening shot of Spike Lee’s Bamboozled features Damon Wayans, playing a thoroughly co-opted buppie television writer, nasally reciting the dictionary definition of “satire”. The movie ends with a montage of racist depictions of African-Americans in the media (take that, Birth of a Nation!). These two scenes probably tell you everything you need to know about what to take away from the movie. Namely that this film is a satire on depictions of Blacks in the media and their own complicity in the process, and also that Spike Lee thinks we’re all idiots. Fair enough. I have really not been much of a booster of the French New Wave cinema of the 1960s. I tend to become exasperated with their intellectual high-mindedness and roll my eyes at their sentimentality. The one exception I’m finding is the films of Truffaut. Unlike Godard and Roemer, Truffaut actually seems to want to make movies, instead of films (actually, I suspect that the pseudointellectual Godard secretly wanted to write Marxist manifestos, and Roemer — who I actually do grudgingly respect — wanted to write really, really boring novels).

I have really not been much of a booster of the French New Wave cinema of the 1960s. I tend to become exasperated with their intellectual high-mindedness and roll my eyes at their sentimentality. The one exception I’m finding is the films of Truffaut. Unlike Godard and Roemer, Truffaut actually seems to want to make movies, instead of films (actually, I suspect that the pseudointellectual Godard secretly wanted to write Marxist manifestos, and Roemer — who I actually do grudgingly respect — wanted to write really, really boring novels). I rented this with no idea there was an

I rented this with no idea there was an