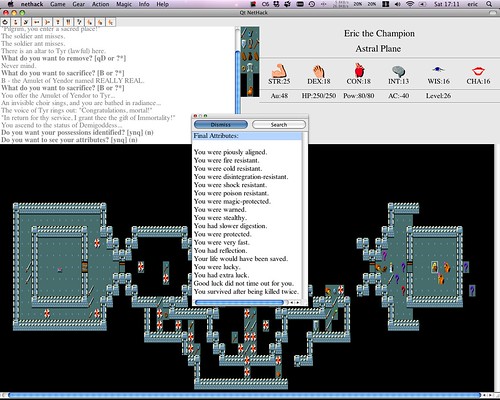

More than 10 years after I started playing Nethack — probably the deepest computer game evar — I finally beat it! That’s a 6,139,426-point Valkrie win right there, homeboy.

If you don’t know Nethack, you’re not alone — it’s a bit of a cult computer game. And like a lot of cults, it represents a fairly fundamental evolutionary offshoot from the main branch. In fact, I’d say it represents a gaming philosophy that’s radically different from what’s now the mainstream.

For one thing, the game has been in constant development for the past 20-odd years. It was started in 1987 as a spin-off of a game called Rogue, which was a crude Dungeons-and-Dragons type of adventure game, developed on UNIX computers using ASCII (text) characters in the place of graphics. In 1988, development was organized by a University of Pennsylvania philosophy professor with time on his hands, that’s when it started to take off. Since that time, the game has undergone countless revisions, as literally thousands of monsters, pieces of equipment and interactions have been added by the secretive DevTeam, essentially making it the product of a decades-long brainstorming session. For example, every potion in the game can be drunk, of course, but it can also be thrown at monsters, or the wall, or the floor — and monsters can and will throw it at you in a pinch (assuming they are intelligent and have arms). It can be boiled, frozen, diluted, or mixed with any other potion — and if it boils you might be affected by the vapour. You can dip your weapons, armour or any other item into it. It can be blessed or cursed. And every interaction has been considered and tested! If you try dipping a potion of acid into a fountain, it will bubble up and burn you instead of diluting. If you dip arrows into a potion of sickness, it will poison them, but if you dip them into a potion of polymorph, it might turn them into darts. A potion of gain level will normally raise your character’s level, but if it’s cursed, it will raise you a level of the dungeon, instead. Nethack likes puns.

One reason it can pull this off is that the graphics are incredibly basic. The screenshot above is Qt Nethack, which is pretty fancy-pants by Nethack standards. The default is just plain ASCII symbols: http://cjni.com/wp-json/wp/v2/posts/742 @ is you, < and > are stairs down and up. A d is a dog that you might be able to tame and even make a pet if you have food for it, but a D is a dragon: there are 18 different kinds, any of which will probably fuck you up if you’re not ready. And you know what? The game is just as engaging as any current-generation console game — more than most, in fact. Funny how the human minds works.

The other way Nethack diverges from current game dev practice is that it is painfully, heartstoppingly, masochistically unforgiving. Whenever you load a saved game, the first thing the program does is delete your saved file. If you die, you don’t go back to the last place you saved. You’re dead. Start over. And you will die lots, especially in the beginning part of the game, when most of the items in the dungeon are unknown and dangerous and plenty of the monsters are tougher than you.

Even worse, the game is fair. Which is to say, play balance has been so refined that death is rarely arbitrary. Most deaths are caused by greed, impatience and/or sloppiness. Sure there’s a point when death is inevitable a few turns away, but looking back, there’s always something you could have done differently if you were smarter or more careful. If you had used your wand of cold to fight the giant bees instead of your sword, you wouldn’t have been poisoned by their strength-depleting stings, which would have let you carry the cockatrice corpse down the stairs without falling on it and being turned to stone. (True story! Also, I’m a huge nerd!) Supposedly, the best Nethack players can win several games in a row without dying, but I died hundreds of deaths between discovering the game in the 1990s and beating it last weekend (and then there was the one time my high-level wizard managed to accidentally leave the dungeon without dying or winning).

All of this — the complexity, the lack of graphics, and the sheer unforgiving brutality — makes Nethack impenetrable and frustrating to most people and intensely interesting to a few. Probably explains why it’s a marginal cult game at best. (It doesn’t help that these days, the game’s mysteries are all just a Google search away.) I haven’t played it much lately — the game I won on Saturday I started over two years ago and played for a couple of hours every few months. But I will say, finally beating this sadistic bastard was a lot more satisfying than getting to the credit screen of any PS2 game.

This article about the power law isn’t new, but it’s been making the rounds at Worio. I really wish I could write like this — it makes an interesting and important technical point and it does so with wit and enthusiasm.

This article about the power law isn’t new, but it’s been making the rounds at Worio. I really wish I could write like this — it makes an interesting and important technical point and it does so with wit and enthusiasm.

A notice to Generation Y: the 1980s were not cool. High school was not like John Hughes movies (except that the seemingly-cool chick usually really did end up with the jock or the rich kid in the end). Nobody wore their legwarmers and teased hair ironically– they were just kind of naive and dumb that way. And the only reason you think that the music was cool is because you listen to things that were never on the radio, anyway, unless maybe you lived in London or New York — it was all Phil Collins and Tom Cochrane and Milli Vanilli. And there was no internet, so even if you somehow heard about The Smiths or The Stone Roses on late-night CBC Radio, you had to go to a record store and special-order a record that *might* show up six weeks later. And don’t get me started on the TV.

A notice to Generation Y: the 1980s were not cool. High school was not like John Hughes movies (except that the seemingly-cool chick usually really did end up with the jock or the rich kid in the end). Nobody wore their legwarmers and teased hair ironically– they were just kind of naive and dumb that way. And the only reason you think that the music was cool is because you listen to things that were never on the radio, anyway, unless maybe you lived in London or New York — it was all Phil Collins and Tom Cochrane and Milli Vanilli. And there was no internet, so even if you somehow heard about The Smiths or The Stone Roses on late-night CBC Radio, you had to go to a record store and special-order a record that *might* show up six weeks later. And don’t get me started on the TV.